Biography of George Nissen

Since this biography was written George Nissen saw the sport he loved on the Olympic stage, first at the Olympic test event in Sydney 2000 and then at two further Olympics. Sadly he passed away on the evening of Wednesday 7th April 2010 (at 7:10 pm) in San Diego due to complications from a bout of pneumonia. His wife & family were in attendance at his bedside as he slipped away.

“The Man and the Kangaroo”

by Jeannette De Wyze – published 13Aug98, San Diego Reader

Imagine that the year is 1930, and you feel like jumping. Your options are limited. You can launch yourself upward a foot or two for a microsecond before gravity pulls you back to the unyielding floor. You can climb onto something squishy or spring-filled: a couch or better still, a bed, and gain a little more height. You can join the circus and ingratiate yourself with the trapeze fliers, get them to let you play in their safety net. But you cannot buy a trampoline anywhere in the world. George Nissen hasn’t invented one yet.

Today, of course, trampolines have become household items. And Nissen lives in an elegant condominium just a few blocks from University Town Centre. He and his wife moved here from Iowa a few years ago to be closer to their younger daughter and her family. Nissen hasn’t retired from inventing things. At 84, he estimates that he still comes up with about one new creation per year. “Inventing is one of the three things that make you happy,” he says. “Working. Loving. And creating.” To his way of thinking, he adds, creations have to be tested in the marketplace and found valuable or else they’re “only partially satisfying.” Public acceptance proves that your invention “was more than just your bullshit. When you see hundreds of kids jumping on trampolines, you know that the idea really was worth something.”

His words are scarcely louder than a whisper. It’s as if the years have worn away Nissen’s voice but left the rest of him unscathed. He’s a small man, still lean, belly flat. Most of his hair is gone, but a baseball cap often conceals this. The skin of his face, rather than wrinkling, seems to have tightened, revealing the underlying skull bone. His slate blue eyes are set deep within their sockets.

His demeanour, like his voice, is quiet. He looks chagrined whenever he thinks he has talked too much. But when asked to recall what inspired his first invention, he says, “When we were kids, we went to the circus, you know, and I got the idea from the nets under the trapeze.” After performing, the fliers would drop into safety rigging, sometimes bouncing up into a somersault or rebounding out of the net with a flourish. It struck George that on similar equipment, a person could perform the complex acrobatics that divers do. But instead of landing with a splash, you could bounce up again and do more tricks. To Nissen, the appeal of this was obvious.

By the age of ten, he’d already become entranced with tumbling. A physical education teacher in junior high school had organized a school gymnastics team, and when one of the team members was sick one day, George volunteered to substitute. “That’s how I got in, even though I was in seventh grade, and it was mostly ninth graders who were doing this. But, boy, it was just what I liked. They had a parallel bar, and I did pyramids on it.” The practice at school won him a place on a YMCA tumbling team that performed at shows all over Cedar Rapids, “generally in exchange for a meal.” The high school he attended had no gymnastics program, nor did it possess a swimming pool. “But the Y had one and the high school was quite close to it. So I got into diving.” When Nissen was a senior and the 1932 Olympics were approaching, he went to Iowa City to get experience on a three-meter diving board. He says he just missed winning a place on the Olympic diving squad.

He graduated from high school at 16, and because he was so young, he didn’t want to start college immediately. Instead, he tinkered with his idea for building a bouncing rig. Besides the trapeze fliers, other entertainers from time to time had custom-built such contraptions. Vaudeville comedian Joe E. Brown, for example, had used a springy table as a platform from which he leaped onto the shoulders of a partner. Brown also had gotten laughs by falling off the stage and then shooting up onto it again, propelled by his elastic table (hidden in the orchestra pit). But Nissen didn’t know this; he just wanted something he could bounce on and use as a platform for gymnastic tricks.

His first impulse was to make the rig round. A round design is “very efficient as far as construction,” he notes. Constructing the frame for the canvas isn’t difficult because the forces on all parts are equal. But a round design is “very, very inefficient in the use of space,” Nissen says. If the elastic bed is big enough so that the jumper won’t fall off, it takes up far more of a room than would a rectangular design of the same length. Something else about the round concept bothered Nissen back in the early 1930s and bothers him today (now that round trampolines have become standard in the consumer market). “You have no orientation when you jump,” he points out. “I’m scared on a round one. Because the vast majority of time, when people do fall off trampolines, it’s at the ends, the long way. That’s the way you orient. But when it’s round, everything’s short.”

Working in his parents’ garage, he began to try to build a rectangular frame. Discarded angle irons from the local junkyard became his building material. Friends helped bolt them together and suspend a piece of canvas from the structure. “At first we didn’t realize that as soon as you make [the framework] a little bigger, there are tremendous stresses on the sides. So it has to be very strong, or otherwise it collapses inward.”

In the fall of 1933, Nissen began classes at the University of Iowa, but he and a few buddies continued trying to build a jumping rig in their spare time. By the following summer, they had one that they took with them to a YMCA summer camp where they had jobs as counsellors. Nissen says that first successful rig “was big and strong and heavy.” It had a bed made out of canvas that they had bought from a tentmaker, cut into shape, and rimmed with grommets. To connect the canvas bed to the steel frame, “We’d taken inner tubes from old automobiles and cut them up about a half an inch or an inch wide. They’re long and thin, and it’s pretty good rubber.” At the Y camp, they erected their creation outdoors, “and when it rained, of course there’d be a big puddle in there and it was just like bouncing in mud. But when it dried out, it was – zing!” His face softens with pleasure at the memory.

Although Nissen and his friends had brought the rig to camp to practice on it themselves, it mesmerized their youthful charges. “In fact, the kids would even stay out of swimming if they could have a turn on it,” Nissen recalls. He adds that swimming in the river provided the only relief from the merciless heat of the Iowa summer. And yet the children would forgo this for the joy of jumping. “Afterward, I began to think, ‘Gee, if kids like this so much, maybe you could make them and sell them.’ “

Nissen says it was clear that any commercial product would have to be both light and portable. So he began to think about how he could change his design to achieve that. Other activities were competing for his time, however. At the university, he’d gotten back into gymnastics and tumbling, and three times in a row he won the intercollegiate national championship. He also competed in Big Ten diving meets as a member of the Iowa team. Because sports consumed so much of his extracurricular attention, he says he didn’t want to major in physical education. Instead, he took classes in mathematics and loved them; to this day his tone grows fervent when he recalls some of his actuarial-science classes. He got a degree in business in 1937. But he wasn’t yet ready to don a suit and join the ranks of corporate America.

He yearned to travel first. “I was inquisitive. And I’d see other people who would work for two years and they’d save up umpteen dollars and go to Europe for five days and come back and that was it.” This seemed pathetic; Nissen figured he could do much more travelling if it was part of his occupation. So he and two college buddies became the Three Leonardos. “We had two basic acts – a hand-balancing act and a comedy tumbling act. We’d get maybe $20 or $25 for the three of us. We’d have to drive 100 miles, but, boy, we thought we had it made!”

Nissen says they performed at various carnivals and fairs. While booked at the Texas Centennial celebrations they heard about a possible gig in Mexico City. “We went on down, and they kind of liked us at one of the big nightclubs,” he says. “We didn’t have any permits to work, so we drove up to the border and drove back down again.” It didn’t take them long to secure other engagements, one at the Palacio de Bellas Artes and another at a big fair in Chapultepec Park. “We didn’t get much money for any of them.” But working two or three jobs, they made enough to survive.

Their living expenses were minimal. They stayed at the Mexico City Y, where the local swimming and diving team worked out every morning. “They had their meets with other clubs on Sunday mornings,” Nissen recalls. “They pulled me right into the team.” He didn’t speak much Spanish, but soon he was fluent in the lingo of the Mexican divers – aeroplano for swan dive and canguro for jackknife and, of course, the word for the diving board itself: el trampolín.

Nissen liked the sound of that word, and when he and his two buddies returned to the United States after about six months, he decided he would Anglicize the spelling and call his bouncing rig a Trampoline, a term he registered as a trademark. Finding customers turned out to be more difficult. Sporting-goods retailers thought the only buyers would be show-business performers, far too small a market to interest them. But Nissen remembered the reaction of the YMCA campers. If he could show people how much children loved the activity, schools and YMCAs would clamor for his invention, he was confident.

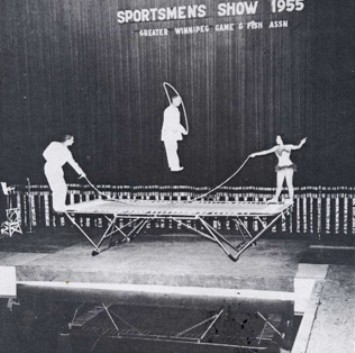

He and the other two Leonardos auditioned before an agency that booked acts into school assemblies throughout the United States, and after a while Nissen says they were getting invited to put on 200 to 300 programs a year. “We had the car and we’d pack it up and do two or three shows a day. We were eager beavers, you know, and we liked the workout. I did a ten-minute talk on tumbling, and I did some tumbling on the stage. Then we did some hand-balancing and some comedy stuff. And then we had the trampoline. We’d have some of the kids come out of the audience, and we’d show them how to jump.” Audiences greeted this with wild enthusiasm.

The idea was to promote the activity and the sport without having to pay sales reps. And slowly, orders materialized, at first from YMCAs and schools small enough to be able to make an independent buying decision. They paid $150 for “a trampoline as large as a living room,” Nissen says. “There were 100 springs in it.” Nissen purchased these from a spring manufacturer. Customers had to assemble the many components themselves.

Nissen thinks he may have sold a total of ten trampolines the first year he took orders. “My father said, ‘Well, you’ve saturated the market. When are you going to get a real job?’ ” His partners, too, had doubts about the future of the business, and eventually Nissen bought them out. “By the time of World War II, I ran the company.”

For a while, it looked as if that might be an empty accomplishment, Nissen says today. “I thought that the war would ruin the business.” Gasoline supplies became tight and tires hard to find. Worse still, coaches who had been on the verge of buying trampolines for their schools were enlisting in military programs that promised to use their skills to transform civilians into fighting units. Amidst the hectic war preparations, however, Nissen wondered if there might be a role for the trampoline as a training tool. “I went to Randolph Field in Texas and I got my picture in the paper, showing the cadets how to jump. I went to Corpus Christi. They were just building that. I went to Pensacola and a lot of places.” He came away with so many orders that he delayed his own enlistment while he set about fulfilling them.

Nissen today points out that those same P.E. teachers who signed in the wake of Pearl Harbour had seen trampolines in action. They could understand how the equipment might help condition pilots and parachutists, in particular. “Every time you jump, there’s two seconds of freedom,” Nissen explains. “Two seconds in which you’re absolutely weightless.” During that interval, twisting your body into exotic postures requires almost no effort. “The feeling is the same as it is in space.” Beyond giving the jumper a taste of weightlessness, jumping on a trampoline builds muscle strength and sharpens the jumper’s awareness of how he’s oriented in space, Nissen asserts.

By 1943, he was able to leave his business in the hands of his brother so that he himself could join the Navy. To his dismay, his assignment took him nowhere near a base that had purchased his invention. Instead, the Navy ordered him to serve as a navigator on a destroyer (in part because of his college math training). It wasn’t until after D day that he got himself reassigned to St. Mary’s Preflight Centre near Oakland, where “they must have had almost a dozen trampolines.”

In all, Nissen estimates that he sold at least 100 trampolines to the military during the war, a period in which the design also evolved. When nylon webbing was developed for parachute straps, he realized it could be woven to create a material that was much stronger and more elastic than canvas. To this day, the beds of competition trampolines use a similar material.

With the end of the war, his first competitors appeared, flogging knockoffs with names like the Acromat and the Tumble-leen. The first national “rebound tumbling” competition was held in 1947, and in 1948 the National Collegiate Athletic Association (nacho) voted to include the activity at its collegiate gymnastic meets. Nissen, who had incorporated his business in 1946, moved it into a barnlike 12,000-square-foot facility in Cedar Rapids. Yet he was often absent from the premises. It was still urgent, he believed, to get his invention out on the road, in front of as many people as possible.

At a Shrine Circus in Kansas City, he came away with something more important than an order. He met an aerial acrobat from the Netherlands named Annie, who impressed him so much that he later wrote her in Europe and asked her to join his act. “She’d never been on a trampoline,” he says. “But she learned the somersaults pretty fast.” The two married in 1950.

Today from a cabinet in her living room, Annie, a petite woman with large, kindly eyes, can pull out albums filled with professional-looking photos that hint at the adventures she and George shared. There’s one of her, lithe and sexy in a leotard, doing the splits ten feet up in the air above a Nissen trampoline set up at a sports show. She looks as relaxed as a yoga student. Another photo shows an adorable preschooler, the Nissen’s first daughter, Dagmar, boarding a small plane decorated with the image of a kangaroo. That was the Nissen company logo, and it inspired what must be the most remarkable photo ever taken of George.

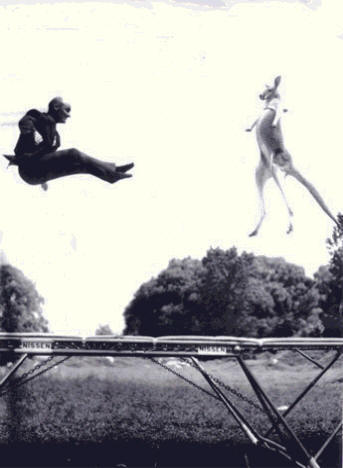

He explains that in his ceaseless quest to publicize his invention, he found a Long Island animal supplier who owned a couple of kangaroos. “I went and asked what it would cost to get some pictures. The guy told me he would charge me $50 [to pose with] one of them and $150 for the other. When I asked what was the difference between them, he said, ‘Well, the one for $150 won’t kick you so hard.’ “

Opting to rent the more expensive animal, “I found out a lot about kangaroos,” George recounts. “That they’re the stupidest things you ever saw. And they like apricots. And you can’t train them to speak of.” Over the course of several sessions with the marsupial, Nissen observed that “if he rides up on his tail, he’s gonna kick. But he can’t kick you while he’s flat-footed. He telegraphs his punch.” By grabbing the animal’s tiny front feet, Nissen says he learned how to manoeuvre the creature out of kicking position. He also found that he could put the animal at one end of a trampoline and by bouncing the other end, start it to bouncing. One time Nissen managed to hop on and jump in tandem with it, and the images captured by the photographer that day are at once comical and astonishing. Both the kangaroo and Nissen (dressed in a dark suit and tie) are frozen high in the air, limbs extended. They look like they’re jumping for the joy of it.

The photo got him in trouble with Macy’s, Nissen claims today. When “the head mogul” of the department store saw the photo, he insisted that Nissen bring his kangaroo act to the opening of a new Macy’s outlet. Nothing that Nissen said could convince Macy’s that no such act existed. “They were so mad at me. They never did believe me!” Elsewhere, however, the photograph proved a publicity jackpot. “I have a box full of newspaper clippings of that picture,” Nissen says. It ran all over Europe, “even in Yugoslavia. People thought it was the funniest thing, and they’d just laugh and laugh.”

By the time the picture appeared, Nissen had embarked on a more elaborate campaign to introduce the world to trampolining. He’d travelled to England a few years after the war ended, and the enthusiastic reception given the jumping exhibitions there encouraged him to take his invention all over Europe. To serve that market, he established a branch of his Nissen Trampoline Company in England in 1956, and around the same time he embarked upon the first of a dozen or more visits to the Soviet Union. Though these took place during some of the frostiest phases of the Cold War, Nissen says he was never frightened while travelling behind the Iron Curtain. “The one thing I always had in the back of my mind was: they need me.” He not only was demonstrating trampolining to the Soviets but also arranging for their athletes to compete in the United States. “I was one of their best keys to the West,” he reflects. “And I saw a lot that would really make you want to be anti-Communist, but I kept myself very clean politically.”

He and Annie and Dagmar journeyed to Japan and South Africa about the same time, and they introduced trampolines in South America as well. There, because of the linguistic confusion with diving boards, the jumping equipment was often known simply as a “Nissen.” Back in the United States, the name of Nissen’s invention was proving more problematic, as competitors began to refer to their products by the word that Nissen had trademarked. “They weren’t supposed to do that,” he points out today. “The real generic term is ‘rebound tumbling.’ And the patent attorneys – oh man! They’d say, ‘You paid this money and you should fight!’ So they had a bonanza for years. They’d say, ‘Well, we had Kleenex and we had Scotch tape.’ You see the object is to let it get almost generic and then pull it back. That’s what they try to do. And we did have a lawsuit against one company, and of course we won that case. But so what? All you do is make a lot of people mad. I didn’t care if they put the R [®] after Nissen or after Trampoline.” In the early 1960s, he decided to let the trademark lapse.

Something else had happened by then that also filled Nissen with conflicting emotions. The first inkling of this turn of events came in the fall of 1959, when orders for trampolines started to arrive from a new source: small operators interested in opening outdoor “jump centres.” San Diego got its first one in late November of that year at the corner of 64th Street and University Avenue, and in its first 40 days of operation, the owner took in almost $3000. Such success ignited interest among others, and within just four months, 20 operators in San Diego County had either opened centres or announced plans to do so. (Among them was world light heavyweight boxing champion Archie Moore.)

In larger cities, the growth was even wilder. “Last fall there were three jump centres in the Los Angeles area,” reported a Life magazine cover story on the phenomenon. “Now [May 2, 1960] there are 175 there and another 150 in Miami, Phoenix, Houston, Oklahoma City, St. Louis, Reno, Hawaii, and other places. Matrons trying to reduce, executives trying to relax, and kids trying to outdo each other are plunking down 40 cents for a half hour of public bouncing at trampoline centres which are spreading the way miniature golf courses spread several decades ago.” Newsweek reported that a plot of land, about $8000 for equipment, and some liability insurance could generate an average gross income of $1500 a month. It added that Nissen expected his company’s gross sales to reach $4 million in 1960 (up from $900,000 in 1957) and was building a $615,000 plant to house his 100 workers. It quoted the Iowa inventor as boasting that the list of backyard jumpers by then included “Vice President Richard Nixon, Yul Brynner, a brace of Rockefellers, auto-TV man Earl (Madman) Muntz, and King Farouk.”

If Nissen felt elated to see his invention at last take America by storm, he fretted over the format of the centres. “We didn’t like them!” he declares today. He says he often grilled would-be operators about how their places would be managed, but they’d brush away his questions. “You just get a girl to take tickets!” they’d say. Financing often seemed to be on a shoestring, Nissen says. And the newcomers were frighteningly ignorant of the dangers faced by untrained jumpers. Part of the pitch, Nissen explains, was that the centres were safe because they featured trampolines at ground level, set into pits. ” ‘You can’t fall off!’ That was the line. Well, it sounds good, but it is absolutely bad,” Nissen says. Trampolines set into the damp ground get wet. “Anyone can walk onto them, with shoes and everything.” And injuries from falling off trampolines have always tended to be minimal, Nissen says. The most cataclysmic accidents happen in the middle of the bed.

And get hurt they did. In San Diego, just days after the San Diego Union ran a long story about “San Diego youngsters from 8 to 80 jumping for joy,” a 15-year-old beauty queen candidate from Coronado knocked out three of her front teeth at a jump centre (forcing her to withdraw from the Miss Coronado pageant and prompting her parents to sue the operator for $52,000). Almost simultaneously, a 16-year-old high school football player from Kearny Mesa was paralyzed at a jump centre on Ulric Street. “He was trying an extremely difficult ‘suicide dive’ after only two visits to a centre and instead of taking the fall on his back and shoulders, hit right on the top of his head with his whole weight on his neck,” the Union later quoted one of the centre operators. After two weeks in the hospital, the boy died.

As the list of injuries – fatal and minor – mounted, the San Diego City Council scrambled to try to regulate the centres. But while the council dithered, the marketplace was imposing a more draconian punishment on those who had sunk their savings into the craze. By late August of 1960, “what went up was plainly coming down,” Newsweek reported. Typical monthly profits had plunged to “a soggy $500,” according to the magazine, and the centres were closing in droves. In San Diego, a year after the fad had begun, the Union reported that “trampolin [sic] centres have joined the limbo of hula hoops, yo-yos, and marathon dancing.”

What could you expect? Nissen asked a Newsweek reporter. “You have to have programs. I bounce myself, but if I didn’t have something new to do on a trampoline, I would lose interest.” Although he didn’t say so at the time, Nissen was beginning to think a lot about how to sustain a broad-based, long-term interest in trampolining. “If you’ve got 50 kids out there on trampolines, well, after a couple of weeks 25 of them are going to be better than the other 25. And the ones that are not so good at it drop out. Later you’ll find there are maybe 12 left. And pretty soon there’s just a hard core.” The same thing occurs in other acrobatic activities, he says, be it springboard diving or figure skating or gymnastics. In the swimming pool, the ice rink, and the gym, however, two other spheres of activity exist: races and games. In the gym, people play basketball (among other games) and they participate in indoor track meets. On the ice, they play hockey and they speed skate. In the pool, they swim races and they play water polo. In contrast, “On the trampoline, we only had acrobatics.” Dissatisfied with that, Nissen says he set about inventing a way to race and play games on the trampoline. (photo left: Nissen sponsored and financed many World Professional Trampoline Championships in the late 1960s and early 1970s.)

The way to devise a game seemed obvious: string a rope across the middle of a trampoline and have players pass a ball over it. This was “fun but rather dangerous,” according to The Oxford Companion to World Sports and Games, “since it was an automatic reaction to dive for the ball when receiving and consequently land near the end of the trampoline.” To make the game safer, Nissen created elastic backstops by adding upturned trampoline halves to each end of the “court.” He also replaced the rope with a net – but “the ball went out of court if passed off centre,” the Oxford Companion records. So Nissen further modified the design, creating a hole in the net through which the ball had to be passed and adding nets to the top of the backstop. “Finally it was found that by diving backward for the ball and rebounding off the backstop net, players frequently collided in the centre of the court. For safety, therefore, the single net was replaced by a double-netted gantry, including a basket rather than a hole, which cambered from the centre so that the ball would never stick in it.”

The sports encyclopaedia says Nissen was “completely enthralled” by Spaceball, as he dubbed the game; today it’s his all-time favourite creation. Set up and demonstrated properly, the game draws youngsters like a magnet, he claims. Some family fun centres still feature a version of it, and they “make oodles of money on it. ‘Cause the kids want to play. And when they’re done, they’re satisfied and they don’t even realize it was good exercise.” He’s also enthusiastic about his marriage of trampolining with track. This was inspired by the development of competitive swimming. Nissen says when he was little, swimmers didn’t swim in lanes. “You were in a lake or something, and you had buoys, and you swam around those, like the boats do.” Then came man-made pools, in which swimming lanes could be set up. Once people figured out how to do flip turns, modern competitive swimming was born. Runners, on the other hand, still think they have to run around in circles, Nissen notes, because they don’t have a way to run in a lane and reverse direction quickly. What they need is a “rebound track” that would enable them to bounce off both ends of the lane. Nissen designed such a track and had sprinters try it, and “they loved the way it felt,” he says. Still, both Spaceball and rebound track would have required considerable promotion, and Nissen says he decided he would be better off devoting his energy to other things.

In the early 1960s, he acquired a line of gymnastic equipment, and he came up with new designs for items such as parallel bars, pommel horses, and balance beams. (Many of the 35 patents that he’s held have related to such refinements, he says, refinements that eventually made his line of gear the best in the world.) And for a while, traditional trampolines still enjoyed momentum. NASA astronauts jumped on them to prepare for space travel. Miss America for 1969 was a champion trampolinist who bounced her way through the talent competition. Throughout the ’70s, Nissen made progress toward one of his ultimate goals: getting trampolining established as an Olympic sport. A breakthrough came when the Russians agreed to include it in the 1980 games in Moscow. “And then along came Carter and Iran and the boycott.” The trampolining competition was cancelled, and although the Russian opening ceremonies featured athletes doing “absolutely phenomenal” tricks on 12 Nissen trampolines, “nobody in America ever saw it,” Nissen says. (photo right: George with friend Astronaut Scott Carpenter. Scott was one of George’s cadet students during World War II in the U.S. Naval Pre-Flight training program.)

Today he says that back in the 1950s, people told him trampolining wouldn’t make it into the Olympics until the year 2000. He used to dismiss such voices as those of cynics lacking vision. But they were prophetic. In the wake of the Moscow debacle, American trampolining entered a Dark Age, he says. The nacho stopped sponsoring competitions. (“The colleges just loved that because they could put more money into football.”) High schools got rid of their trampolines, often citing liability concerns (even though Nissen grouses that rings and high bars have always been more dangerous).

As a result, other countries now produce the stars of international trampolining competitions. Nissen says the drop in U.S. activity has been so precipitous that it’s possible no Americans will make the cut to compete in the 2000 Olympics. There – once again – trampolining may get a chance for permanent inclusion in the quadrennial games. If the public likes the “exhibition competition” scheduled for Sydney, Australia, trampolining most likely will be included as a regular gymnastics activity in the future.

Carter instead competed as a gymnast while getting a degree in physical therapy, but he also jumped on trampolines while growing up in Texas. (“About 75 percent of the competitors in the United States come from that one state,” he notes.) He moved to San Diego in 1984 but says he stopped paying attention to trampolining for some years. Only when he took his first child to gymnastics classes did he think about the absence of any serious trampolining facilities in San Diego County. In 1994 he opened the local tumbling and trampolining school.

It’s one of only four such places in all of California, Carter says. On a Saturday morning, sweaty activity fills it. High school cheerleaders spring into cartwheels on a 120-foot-long tumbling floor, then sink into splits with languid grace. Nearby, Carter has erected a 40-foot-long “tumble-tramp” – a long, narrow trampoline with tumbling mats adjoining either end. Cheerleaders and gymnasts work out on it to hone their tumbling skills, along with a host of athletes from more surprising fields: springboard divers and figure skaters and snowboarders and in-line skaters. Two full-size competition trampolines, so springy that “they’ll just about bounce for you,” according to Carter, also line one wall. On these he guides novices through the steps of learning trampolining tricks with names like “straddle jump pike” and “Barani tuck” and “porpoise free.” Other folks pay between five and ten dollars an hour to jump on the trampolines just for pleasure. This latter group includes Nissen and his wife; their younger daughter, Dian (a 37-year-old fitness instructor who was a champion trampolinist as a teen); even Dian’s two-year-old son. (photo left: George with daughter, Dian)

None of the equipment at Carter’s facility was produced by the company Nissen founded. Finding such a trampoline “is like finding a good old Mercedes,” Carter says. “They were the best! He had special ways of nickel-coating the metal and stuff like that that the manufacturers just won’t spend the money on anymore.” But Nissen’s enterprise ceased to exist in the early ’80s. Today the inventor offers only a brief, weary summary of what happened. The downfall started in the late ’60s, when corporate mergers began to proliferate. “We were kind of a target of a lot of bigger companies,” and in 1972, the board of directors decided that “it benefited the stockholders to merge with Victor Comptometer Company,” a Chicago-based forerunner in the computer field. Five years later, a much larger company, a New Jersey fire-extinguisher manufacturer, acquired Victor. “They took the heart and soul out of the business,” Nissen says. This company eventually lost all interest in trampolines and sold the assets to a German manufacturer.

Nissen made some other mistakes after he left the manufacturing arena, he acknowledges. He became the owner of the Iowa Cornets women’s basketball team. “And I really put my heart and soul and money into it.” The team was good, he says; it travelled all over the United States. Now that women’s basketball is booming, Nissen says people often call him and comment that he was one of the first to promote the sport. But back when he owned the team, two terrible consecutive winters kept fans at home, and the league eventually folded. Nissen also got involved with the movie business but came away disgusted by the calibre of some of the people he was dealing with. None of these business disappointments, however, extinguished his passion for inventing.

His more recent brainstorms have taken him in a number of directions. About ten years ago, he came up with a design for padded bleachers that fold up to create an attractive padded wall. (The seats are more comfortable to sit on, and when collapsed, the padding protects players who crash into it.) Nissen says the system already is in use, and last year he signed up with a company that he thinks may be more aggressive about marketing it.

Even more successful has been his Bunsaver Air Cushion. Nissen thinks he dreamed up this design four or five years ago. “To invent something, you have to have a need,” he says. What triggered his thinking in this case was a complaint from one of his daughters about the hard seats at a sports event they attended together. She suggested he invent some form of padding for the individual spectator. Nissen came up with a self-inflating cushion that’s stowed in a fanny pack but, once inflated, is strong enough to support a truck. Not only sports fans, but also hunters and fishermen have discovered it, and now it’s produced and marketed by a hunting-specialty outfit in Iowa.

Most recently, Nissen has been preoccupied by an invention intended for a very different setting: namely, the seats on a commercial airliner. He says he’d read about the physiological hazards posed by sitting for hours in cramped airplanes, and he began wondering if he could come up with something to help air travellers get exercise. “A stationary bicycle provides some of the best exercise available,” he says. “So I analyzed: What is a stationary bike? Well, it’s just a seat that you sit on, and you have to be steady, and you pedal. But if you’ve already got a [airline] seat, why not use it?” To create the pedals, he made a belt that snaps around the traveller’s waist and connects to a cord fastened to a pulley. Another cord runs through the pulley, and you put your feet into two loops at each end of it. “Now I can push as hard as I want to!” He demonstrates the device, moving his feet in a smooth circular motion. “It duplicates the action of a bicycle.” The straps also can be rearranged to work the arm muscles. Nissen thinks individual consumers might purchase his Laptop Exercycle (as he’s dubbed it), but he’s hoping airlines will consider offering it as an amenity – say to business or first-class passengers. He says he’s talked to someone at Swissair who seemed to like the idea, even though the design was then at a rudimentary stage.

Nissen is continuing to refine the design of the portable exercise equipment, and he says he’s learned that this process takes time. “I call it the 40-40-20 rule.” You get a project to what you think is a state of perfection. But you always discover that roughly 40 percent of what you’ve designed into it wasn’t really necessary. Another 40 percent needs to be changed to address problems you didn’t foresee. Only 20 percent is really the way you want it. So you go back and tinker with the 80 percent that needs fixing. “And then you get another 40-40-20 the second time, see. But you’re gaining on it,” he explains. That’s why it takes four or five iterations to develop something. “You try to anticipate everything. But you can’t.”

Nissen has given a lot of thought to the fundamentals of inventing. He says the biggest thing is “to find a customer. That’s a broad term. But what I really mean is to find a need to be filled or a problem to be solved.” Then you “think and think and think” about how to do that. “It’s always in the back of your mind or your subconscious.” He says it helps to know something about the field in which you’re working. Essentially, he adds, every invention is “a rearrangement of well-known things to get an unusual result.”

Sometimes clutter helps the process. “If you’re real organized, that stifles creativity,” he believes. When a person is organized, his mind is often closed to the things he’s filed away. Nissen contrasts the super-organized managerial type with the child who’s surrounded by clutter and from time to time startles adults by pulling together disparate elements. Children have “tons of creativity,” Nissen says. “But after a while, it plateaus off. By the time you’re in college, it begins to decline.” To buck that trend, “You’ve got to watch kids. You learn from kids. And sometimes you have to act like a kid. That’s a great help.”

He still does handstands. Almost all children can do them, he points out. “But after a while, there aren’t so many adults who can.” When Nissen was about 65, however, it occurred to him that he never wanted to lose this ability. “I decided it was an important thing to me. It was my trademark.” He studied just how he did a handstand, analyzing the separate elements of the action. And he concluded several things. “You have to keep in good shape. You can’t be too heavy. You have to have strong wrists. And you have to stretch. A couple of years ago, I fell and got hurt, and it was hard to get back on it.” But recover he did.

Nowadays he does five to ten handstands a day, usually in his condominium. He puts his palms flat on the ground and keeps his elbows stiff. His legs scissor up in a steady, smooth action that looks almost as easy as raising one’s arms overhead. Sometimes he goes to a nearby park, gets up on a picnic table, and does a handstand on it. Children are drawn to him then, he says. They’re impressed.

On occasion he does his handstand in front of a bigger crowd, like the one that gathered in Switzerland last August for the annual Nissen Cup competition. Back in 1958, Nissen started this event to help promote trampolining. Men and women from all over the world compete in it, performing tricks that every year seem to grow more ambitious.

During last summer’s event, Nissen was called to the centre of the gym and someone turned on a video recorder. In the tape, he holds himself erect as he acknowledges the cheers of the crowd. He’s dressed like a typical sports official, in a jacket, dress shirt, and tie. He might be taken for a well-preserved man in his 60s. But then he stops talking and makes his way to one of the trampolines. He slips out of his loafers and swings up onto the elastic bed, and as he does so the applause grows loud and rhythmic.

First, Nissen sashays over the apparatus in the slow, bouncy manner possible only on a trampoline. He looks boyish and insouciant – as if the jacket and flapping tie were a joke. He settles into the centre of the bed and drops to his seat, then bounces up to his feet again. He gains some altitude and a few seconds later swings his feet up over his head, bringing them down again with easy grace. The crowd by now is whooping and cheering.

But when Nissen climbs off the trampoline, he isn’t quite ready to stop. He strips off the jacket, frees the tie from around his neck, and flings it to the ground in a virile, exuberant motion. Then he positions his palms and swings his body upward, balanced over his hands. Nissen’s joy in showing off is apparent. But there’s also thought and work built into the handstand. There’s a touch of defiance, too, that makes those who see it screech and stomp the ground and whistle and laugh with delight.

© Jeannette De Wyze 1998